William Cox my 6th great grandfather (paternal) was born December 11, 1692, in New Castle area of the Delaware colony. William was the brother of Thomas, Richard, John, Ann, and Amy Cox. He married Catherine (Katherine) Kinkey (Kinkay, Kankey) in 1716 in Hockessin (pronounced HOE-kessin), New Castle, Delaware. (Katherine’s sister Mary was the mother of Herman Husband, a key participant in the Regulator movement prior to the Battle of Alamance in 1771.)

According to the Delaware American History and Genealogy Project, William Cox (Cocks) acquired 300 acres from William Penn’s daughter, Letitia, and her husband Aubrey. Some researchers have stated the February 8, 1713 date listed by the Delaware History Project website is incorrect, noting that 1713 is when Aubrey and Letitia authorized a law firm to begin selling tracts of land. The property was described as”

“Scituate lying and being in the said county of New Castle beginning at a post Standing in the line of Henry [Dixon] thence East by the lands of the said Henry Dickson, William Dickson and Thomas Dickson two hundred and fifty-three perches to a hickory Tree then North by a line of Marked trees one hundred & Ninety Perches to a hickory tree thence West by a line of marked trees two-hundred and fifty three perches to a post, thence South one-hundred and Ninety perches to the place of beginning containing three-hundred acres.”

William paid “eighty-six pounds of lawful money of America” for the 300 acres, plus agreed to a yearly payment of “three shillings money of Great Britain…on the first day of March forever.” He purchased 50 more acres from Henry Dixon in 1725, giving him a total of 350 acres. His tract was located east of today’s downtown Hockessin, bordered roughly by the current Old Wilmington Road, Meeting House Road, and Benge Road. William’s brothers John, Thomas and Richard lived on adjacent farms in London Grove Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania, by 1722, with Amy close by.

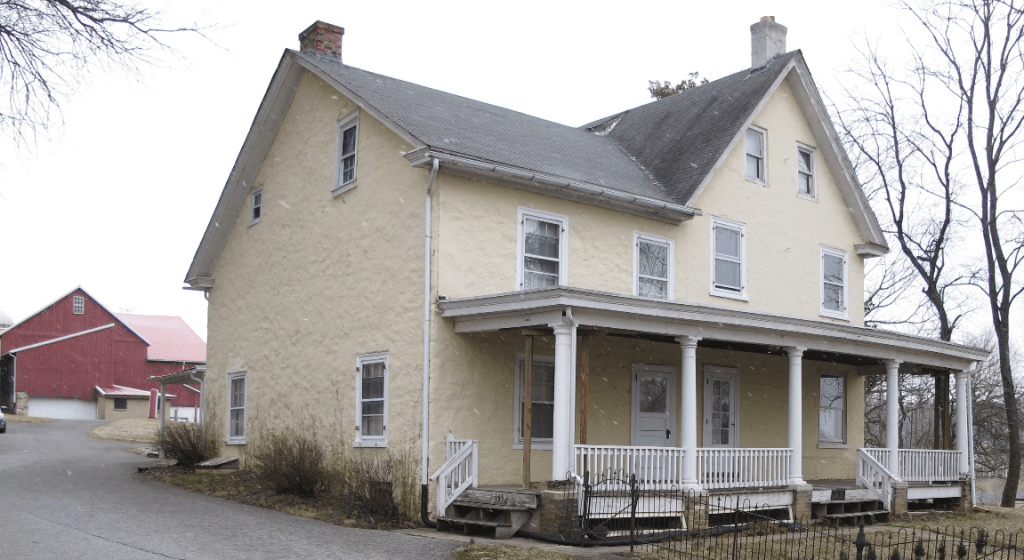

William and Catherine lived in a smaller log or frame house the first few years, but that changed in 1726 with a new brick house William called “Ocasson.” It was a 2-1/2 story, three bay house that faced south looking over his property. In a 2016 interview, current owner Pete Seely notes that Cox built his house near a Native American encampment known to have existed in the area. Quaker leaders had established good relationships with local tribes for several decades, and there’s no evidence of conflict with the Cox family.

The brick date-stone William and Catherine placed in the wall is still on the house and can be viewed from inside a room in one of the later additions. The house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2017.

Some Delaware historians suggest the “Ocasson” name is a misspelling of or mistake in transcribing “occasion” as multiple spellings of the word can be found in records of the 1700s. At some point and “H” was added to form the what is today’s name of the local town “Hockessin.” No variation of Hockessin was being used prior to the arrival of William Cox.

A historic marker dedication took place on September 24, 2020, at the Cox-Phillips-Mitchell House at 1655 Old Wilmington Road.

William was an active member of the Society of Friends. He and Catherine were initially members of Newark Monthly Meeting, later renamed Kennett Monthly Meeting. The first mention of William in those Quaker records was on December 25, 1721 when he was among the witnesses at a wedding.

In 1730, the Quakers in the area petitioned to be allowed to hold meetings at William’s house. What would become the Hockessin Friends Meeting, the first in the vicinity, got its start in the front room of Ocasson. By 1737 the meeting grew too large for the Cox family’s front parlor, and a new meeting house was erected on land donated by William and Henry Dixon. The first written reference to a name for this meeting, “Hocesion”, was likely a variation of “Ocasson”, the name of William Cox’s home.

The November 7, 1953 edition of the Wilmington Journal has an article describing a “small meeting house” built “of whitewashed stone” in 1738 on the donated property, and a “frame addition was added in back in 1745. The eaves have a deep overhang, and there is a small hood over the entrance.” It was described that on “meeting-day the Quakers descended from their horses and carriages by means of a high stepping-block; the big stone with its four steps is still there, and so are the long, low carriage sheds in the rear.”

William and Catherine had ten children: Rebecca (1717), married John Dixon; Mary (1719) married James Lindley; Martha (1721), married William Ferrel; Harmon (1723), married Jane John; Margery (1724), married Isaac Nichols; William Jr. (1726), married Juliatha Carr; John (1728), married Mary Scarlett; Solomon (1730), married Ruth Cox (often confused with Naomi Hussey); Catherine (1732), married Eleazer Hunt; and Thomas Cox (1736), married Sarah Davis.

Quaker records are quiet regarding William’s wife Catherine. I have yet to find a mention of her death in the records, but is presumed to have died before 1752 and William’s move to North Carolina. (Catherine is not recorded as having been received by Cane Creek Monthly Meeting.) She may be buried in the Quaker burial ground at Hockessin, on land provided by her husband. Some family trees on Ancestry.com suggest Catherine is buried in the Old Stone Graveyard in Randolph County, but that seems highly improbable as there is no mention of her being accepted in an area Quaker Meeting.

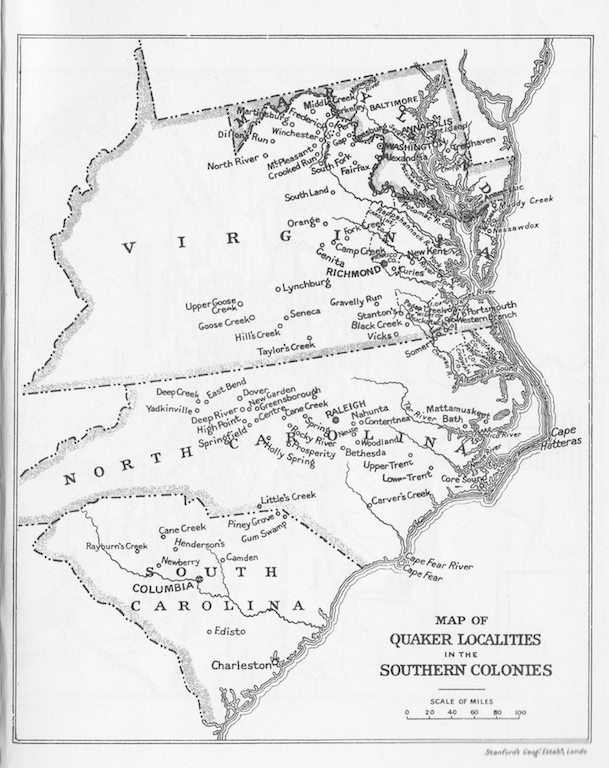

Quaker records show on “1752, 4 Jul (7th mo.) William Cox received certificate from Newark Monthly Meeting, of Kennett Meeting, Chester Co., PA, (to be presented) at Cane Creek Monthly Meeting.” The records further note “1753, 3 Feb (2nd mo.): William COX received at Cane Creek Monthly Meeting, NC, from Newark Monthly Meeting, Orange Co., NC.” His daughter Catherine and Eleazer Hunt petition the New Garden Friends Meeting for marriage in 1752. It’s reasonable to conclude William and his some portion of the family moved to North Carolina sometime around (and before) that time.

New Castle County deed records show the William Cox property being sold to “John Dixson” May 11, 1755 “excepting 1⁄2 acres & 26 perches where the meeting house stands.” John Dixon is the husband of William’s oldest daughter Rebecca.

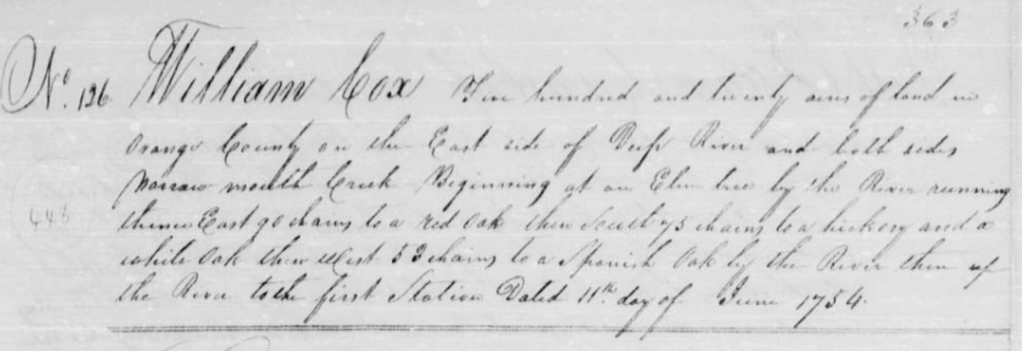

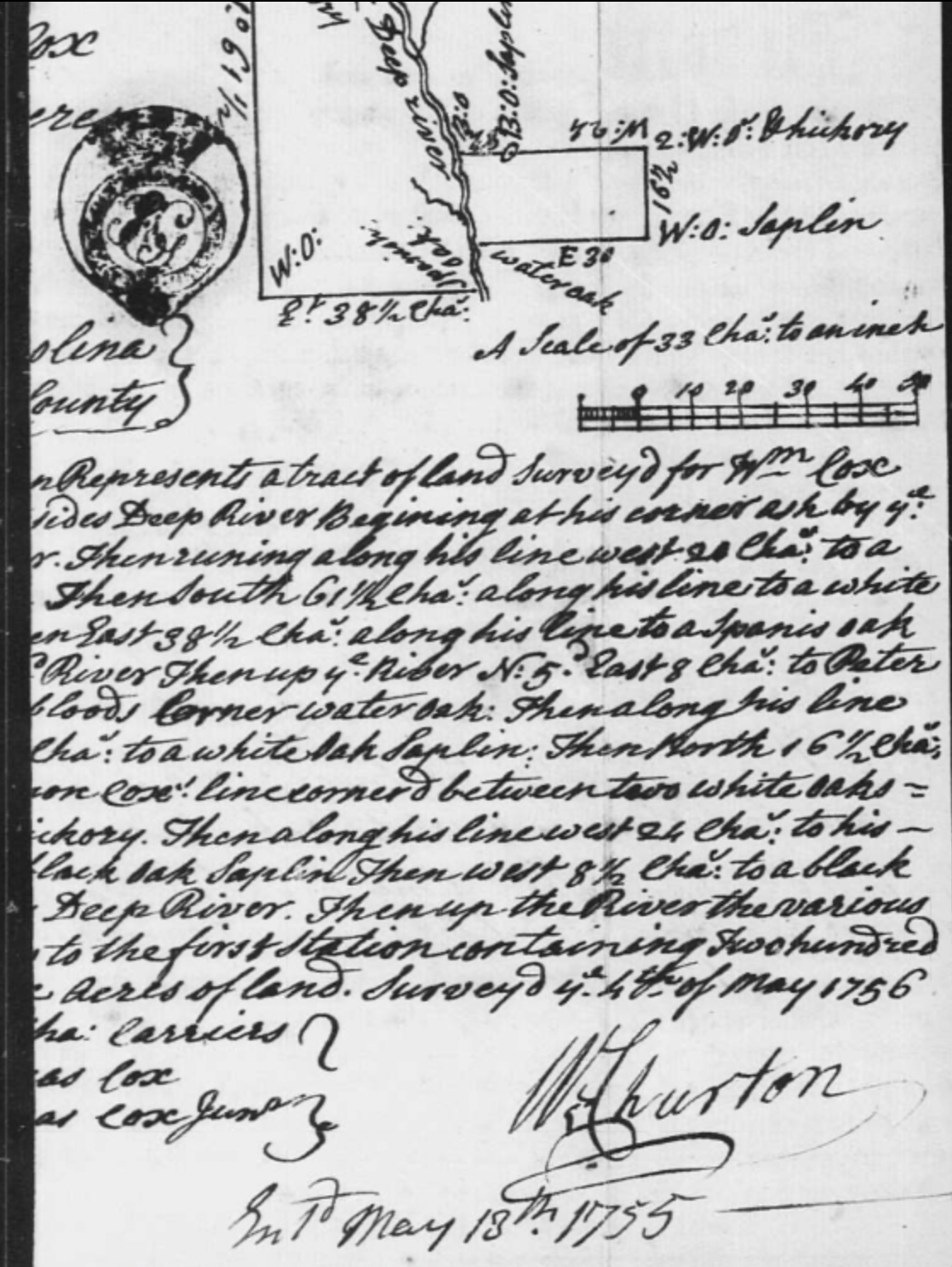

By the middle of the 1700s, when the Indian wars were over, John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville, began offering land tracts from his vast Carolina holdings at bargain prices. The earliest land grant for William is in 1754 for 520 acres “on the east side of Deep River and 400 on the west side. In September 1755, William purchased 180 acres from William Piggot (Piggot) on Cane Creek.

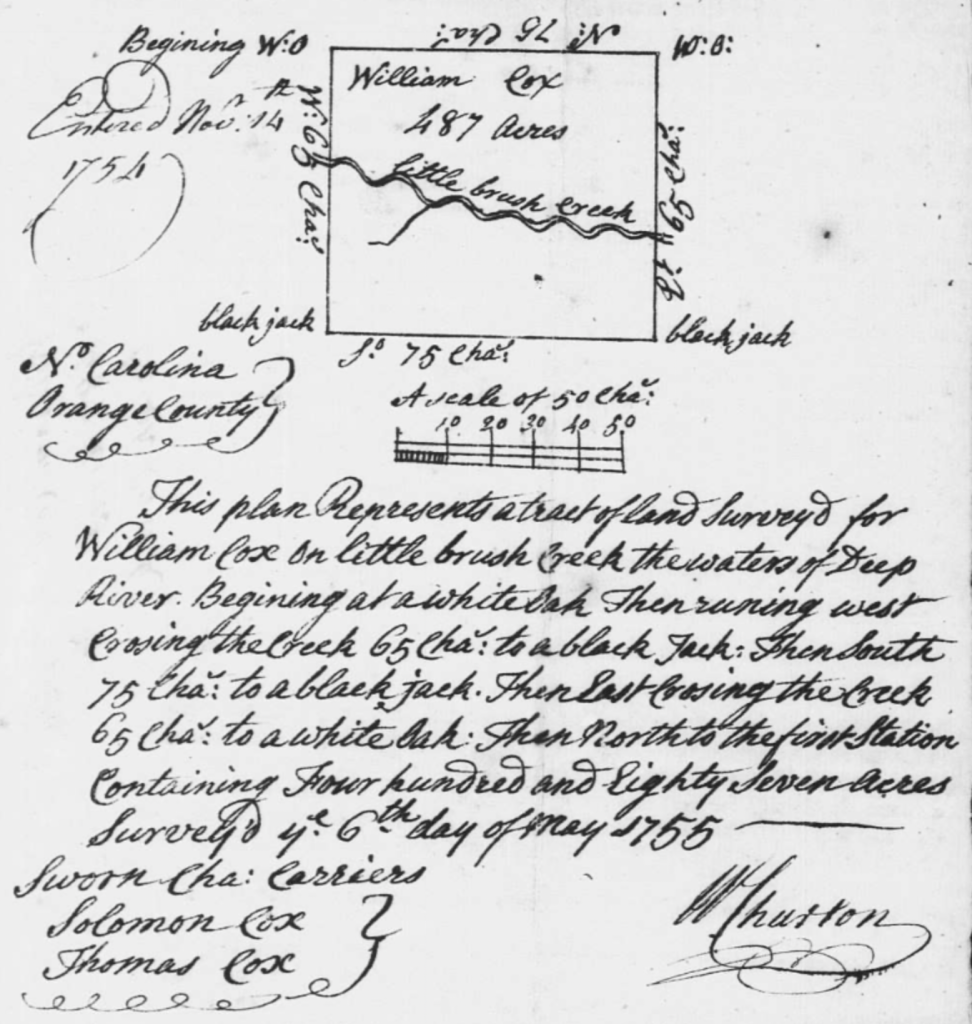

Additional grants were secured in 1755 for an additional 586 acres on Deep River and in 1756 for 487 acres on Little Brush Creek. Three grants were added in 1757 for 205 acres on “both sides of Deep River,” 397 acres “on both sides of Cox’s Creek,” and 375 acres “on the head of Cox Mill Creek.” He sold the 375 acres to his son Harmon in March 1759, and purchased 428 acres from Hugh Smith in the same month. His last recorded land grant was in 1760 for 350 acres “beginning at three sweet gums by New Hope.” William’s sons are also accumulating land and the family became one of the largest land holders in the Deep River region.

John Spencer Basset, Professor of History at Trinity College, wrote described the area in 1895:

“The life of the people was that of the pioneer. The necessaries of subsistence were plentiful, but luxuries were few…there was not a plank floor, a feather bed, a riding carriage, or a side saddle within the bounds of their acquaintance.”

William and his sons built a mill on Mill Creek near where it empties into the Deep River. The mill was known as Cox’s mill, where they ground wheat, corn and an assortment of other grains for neighboring farmers.

The Cox family became associated

with what became known as the

Regulators. William E. Cox (not to be

confused with William, Jr.) wrote in his

work Descendants of Solomon Cox of Cole Creek, Va.

“William Cox and his five sons were loyal Quakers and sturdy pioneers with a deep love for liberty, but they would not hesitate to contend for their rights, even to resort to force, if it became necessary, even though their Meetings forbade such actions. William and his sons were Regulators, a body of citizens who under the name of Regulators, were trying to obtain less extortionate fees from the king’s officers.”

Sometimes referred to as the Regulator Uprising, War of the Regulation, Regulator Rebellion or Regulator War, during the period 1764-1771 settlers in the central part of North Carolina were dissatisfied with the wealthy eastern North Carolina officials that held most government offices, particularly for the levy of what they considered unreasonable taxes and fees.

William’s brother in law and fellow Quaker, Herman Husband, was one of the key leaders of the Regulator movement, and the Cox sons and cousins were involved in a growing organized dissent. (While Harmon Cox is most notable among the combatants at the Battle of Alamance in 1771, brothers Solomon and William, Jr. almost certainly fought as well).

Cox’s Mill was the site of Regulator meetings, and William and his sons were among the signers of Regulator “advertisements” sent to the governor.

Records in the minutes of the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting indicate William and his sons Harmon, William, Jr., and Solomon were all disowned in January 1767 for attending the wedding of Herman Husband and Amy Allen. (Husband had previously been disowned for taking issue with a church decision.) That William and his sons risked Quaker ire to attend Husband’s wedding is an indication of their loyalty to a friend and the Regulator cause. However, William did not live to see the culmination of the argument with Crown’s Governor Tryon.

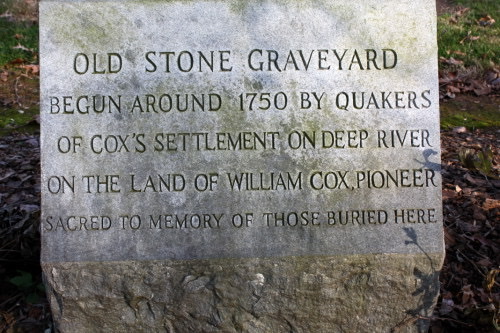

William died on Jan 20, 1767, and is buried at the Old Stone Graveyard just off Highway 22 South of Ramseur, North Carolina. His will was filed in Orange County Court: “Cox, William – Will Book A/53 Will of William Cox, dated 20 Jan 1767, proved Feb 1767.” (Note: the primary purpose of a will in Colonial America was for distribution of property more specifically than common law inheritance rights provided.)

The Old Stone Graveyard of Mill

Creek Friends is located at the

southeast corner of 1871 Mill Creek

Road and contains around two

hundred graves located on land

originally part of the very large estate

acquired through land grants and

purchases by William. This cemetery

is also the resting place for many of

his decedents.

The Mill Creek Friends Cemetery is called the “Old Stone Graveyard” because most of the graves are marked only with unlabeled markers or stones from the area. Some stones have been moved by people not realizing they were grave markers. It is still maintained by Holly Spring Meeting. (Note: Mill Creek Preparatory Meeting was established in “Cox’s Settlement” in the 1750s or 1760s, as an outgrowth of Cane Creek Friends Meeting. About 1790, a new group, Holly Spring Preparatory Meeting, was established and became an independent Friends Meeting.)

Sources of note:

- Colonial & State Records of the South (UNC)

- Lute-Bramblett Family Blog

- The Mill Creek Hundred History Blog

- U.S. Hinshaw Index to Selected Quaker Records (Ancestry.com)

Land Grant files:

You must be logged in to post a comment.