(Featured photo above by Mindy Love from her Sweet Tea & Pasta blog.)

This post is a bit of a work in progress and will most likely be updated several times, but I’m sharing it now as it’s been sitting in draft status for a while. The topic came up in an email exchange a while back with my cousin (and family historian) Emily Cox Johnson regarding a school in the “Cox Settlement” area. I’ve heard stories of an old school and even recall my dad mentioning it on a few occasions but was too young and uninterested at the time to consider the origin or location. I’ve accumulated bits and pieces of info on the topic and will share what I’ve learned so far.

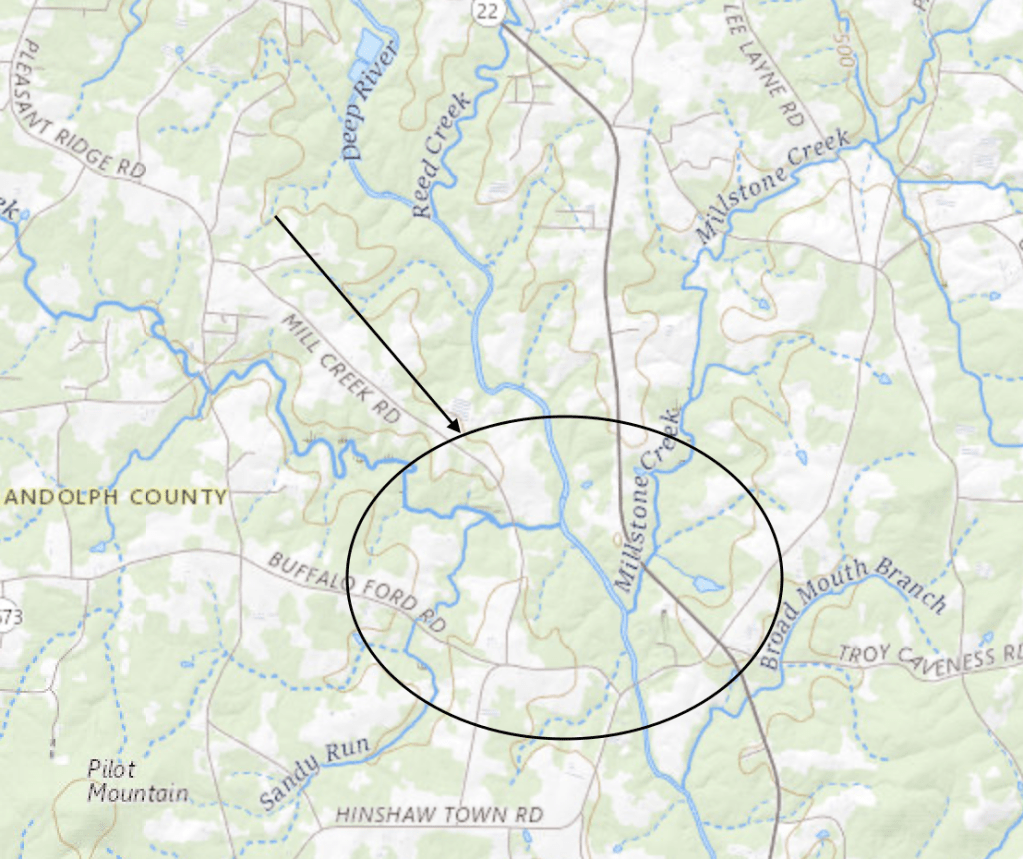

First, where and what is Buffalo Ford?

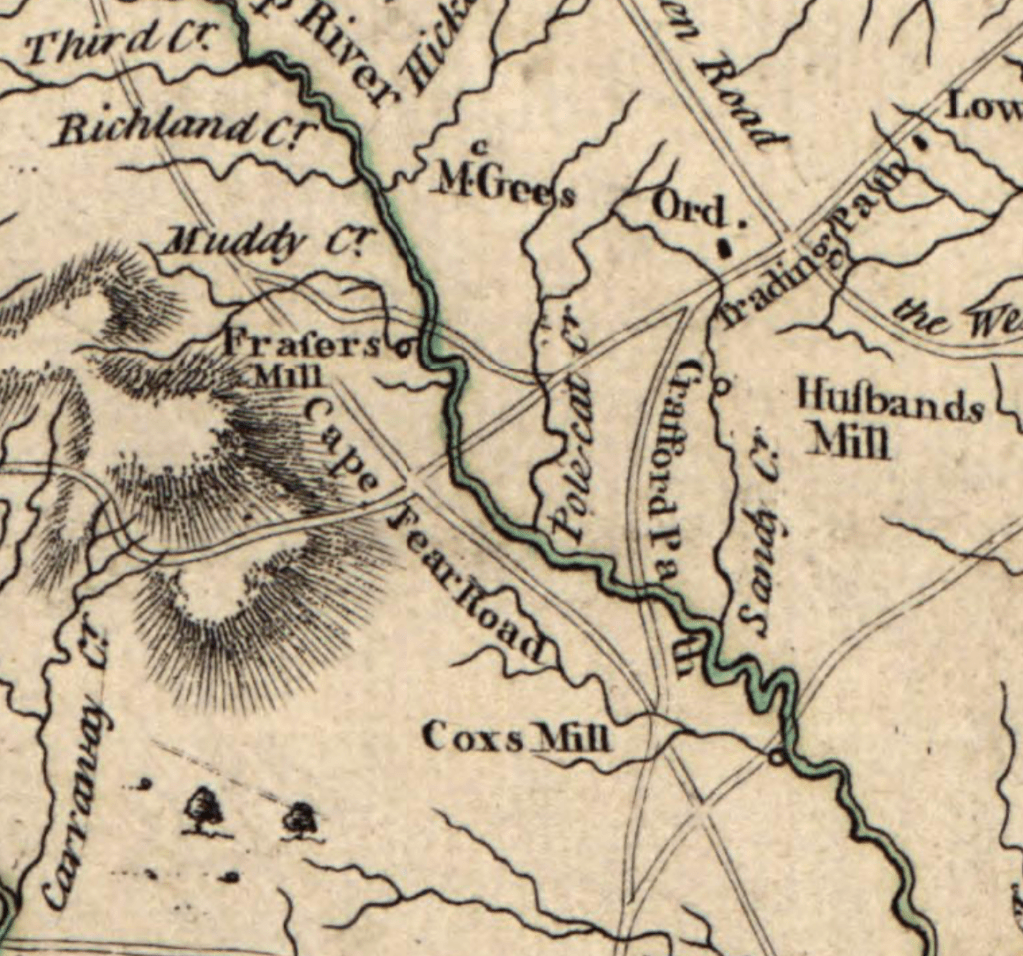

“Buffalo Ford” is a local name for an area on Deep River between Ramseur and Coleridge in southeast Randolph County. Buffalo Ford, Cox’s Mill, Cox Settlement, and Holly Spring were terms commonly used by settlers to describe this section of the river and its tributaries in the 1700s and early 1800s. However, when a local says “Buffalo Ford” they usually mean a more specific area where Deep River, Mill Creek, and Millstone Creek converge.

The actual Ford is where buffalo, native peoples, and settlers crossed the Deep River before a covered bridge was built in the 1800s. (Yes, actual buffalo crossed here. English naturalist and explorer John Lawson described North Carolina as having “plenty of buffalos” in his A New Voyage to Carolina.) The Randolph County Historic Landmarks Preservation Commission notes the location of the Ford as being where the road from Salisbury to Cross Creek (Fayetteville) and Wilmington crossed the road from Hillsborough to Camden, South Carolina.

Randolph County historian Mac Whatley writes:

“As to be expected of such a major river crossing, several related historic sites are located within a mile of Buffalo Ford. The area was known as Cox’s Settlement by the early 1760s and its vicinity includes the Thomas Cox and Harmon Cox mill sites, scenes of much activity during the Regulation and Revolutionary War. David Fanning’s Tory headquarters, known as “the Fort of Deep River at Cox’s Mill” was nearby. Fanning carried out several ambushes at the Ford and fought skirmishes with Patriot militia there while headquartered at Harmon Cox’s Mill from 1781-82.”

Buffalo Ford/Cox Settlement was also where the Continental Army camped and foraged during the summer of 1780 while it waited for the arrival of General Horatio Gates.

This Cultural Heritage Site Nomination written by Warren Dixon provides a detailed history of Buffalo Ford.

Buffalo Ford schools before the Civil War

According to Emily:

“A schoolhouse once existed a short distance east of Buffalo Ford on the John Pope farm. It was most likely a log building. There were no public schools in North Carolina at that time so local citizens would have been responsible for securing a teacher and getting books for students. The John Pope farm was somewhat of a community center. It had a country store, schoolhouse, and in 1850 a post office. John Pope was the first postmaster. Braxton Craven (1822-1882) attended this school when he was at the Nathan Cox house. Braxton had left the area by 1840 so the school was established before that time. Granddaddy Cox (Clark 1861-1938) also attended this school.”

John Pope is indeed recorded as having a “peddler and retailer license” in Randolph County, so it makes sense he had a store of some sort. In 1850 a Buffalo Ford post office was established and Pope was named postmaster (most likely because his store served as the post office). However, I have yet to find specific documentation of a school at the Pope farm or store.

In the Life of Braxton Craven, written by Jerome Dowd in 1896, Braxton’s teacher is identified as Jack Byers “who held forth in a log house about two miles away.” I can’t find any record of a Jack Byers in Randolph County during that period, but the description of a log house two miles away sounds a lot like the John Pope farm which was a few miles south of Nathan Cox.

The 1943 publication Historical Sketches of Southern Quarterly Meeting of Friends states “From the early days of Holly Spring as a Monthly Meeting a school was held under the direction o:f the Meeting, The school house stood about a hundred yards south of the first log Meeting House, Braxton Craven who was to become the first president of Trinity College, now Duke University, was a teacher for one term.”

Educational opportunities were primarily by religious congregations such as the Moravians, Presbyterians, and Quakers, or at academies that were essentially “pay-as-you-go” institutions. Union Institute established jointly by Quakers and Methodists in 1839 near the town of Trinity is an example. It became Trinity College in 1859 and moved to Durham in 1892.

Very little attention was given to public education until the successful Education Act of 1839 and the opening of the state’s first common (public) school in Rockingham County in 1840. Over 2500 public common schools in North Carolina opened during the next two decades, but the Civil War brought this progress to an end. Only a handful of public schools still operating by the war’s end.

The Civil War and after

Fernando Cartland’s book, Southern Heroes: The Friends in War Time (1895), mentions a school near the Holly Spring Friends Meeting during the Civil War. “Just across Deep River from the settlement, and not far from the Friends’ meeting house, was what the people of the neighborhood called the “Bull-Pen,” a rendezvous for the home guard. An old school house was used as a prison for the parents of these men of legal age, whom the guards could not find.”

The location is consistent with the aforementioned Holly Spring school. Whether it was used as a “prison” is debatable. Whatley writes “The schoolhouse at Buffalo Ford was apparently used as a regional headquarters for the Home Guard, a base for their searches for conscripts and deserters, and a detention center for those captured.” However, Whatley emphasizes “apparently” and notes a lack of specific information to be certain the school was used for detention.

What is certain is that Quaker families were harassed during the Civil War because of their pacifist beliefs and opposition to slavery. Quaker farms were raided for supplies by soldiers and neighbors supporting the Confederacy were suspicious of Quaker loyalties. Recognizing the hardships of southern Quakers, northern Friends rallied after the war to provide aid, conduct missions, and support the establishment of schools after the war. Evergreen Academy in Buffalo Ford near Holly Spring was one of five local schools under Holly Spring’s supervision, all within walking distance for children in the area.

The Holly Spring meeting minutes for October 1865 cite the assignment of members to find a location for what would become Evergreen Academy. “This meeting appoints Thomas Hinshaw, David Cox, Elias Macon, Charles Cox, Levi Cox, G.W. Wright, Isaac B. Fesmire, Elias Hinshaw, Jeremiah Piggott, Sen., Neri Cox & Michael Cox to look out for suitable places for schools and also to set up schools among us as thought best.”

In 1866 a site a couple of miles east of the meeting house was donated by Thomas Hinshaw, and Levi Cox (and perhaps others) provided “lumber for the school house.” The school began operation a short time later and continued operating into the 1900s. The structure is still standing and part of the Hinshaw farm on Hinshaw Town Road a little over a mile south of the Ford.

Here’s how Randolph County photographer Dan Routh eloquently describes his visit to the small one-room structure:

“While all the desks and other artifacts have been removed (except for a lone chair and a few boards and tools), the school building has been basically untouched since it was last used. I walked in and immediately saw the chalk letters on the boards that are one hundred years old and remain unchanged since the moment they were written. It was like opening a time capsule. The writing is on blackboards. I use the plural because there is no slate, but rather the wall boards are painted black. Standing in front of the boards, you can almost hear the children that once studied here with an interior space that could be partitioned into two classrooms.”

Local resident Tom Allen video documented the Evergreen structure in 2011.

More schools were eventually built in the area and children on the opposite sides of Deep River attended different schools. Emily notes:

“Around 1872 there was a ‘Mill Creek School’ with a Buffalo Ford address. A lot of the land was owned by the Allen family so most likely it was on some of their property and they were involved with the school. This school would have been across the river (west) from where we live. Mill Creek runs into Deep River from the west side of the river. By the time Clark’s children were ready for the school, a Parks Cross Roads school (east of the river) had been established. It was in session around 3-4 months. It was not mandatory that children attend school so they could quit anytime. My father said they crossed Millstone Creek using a footlog. If they wanted to go to high school, tuition at Ramseur was $2.00 a year.”

In 1881 Thomas Hinshaw provided land for a schoolhouse near the Holly Spring Meeting House. The small frame school building was known as the Center Graded School, and later Holly Spring School, but its common nickname was “Rabbit Gnaw” school. The school had no sanitary facilities and water came from a nearby stream. I have read there was also a small school for black children near the Holly Spring school.

I will update this post as new information surfaces.

Sources of note:

- Randolph County Historic Landmarks Preservation Commission

- Dan Routh Photography

- Notes of the History of Randolph County

- My wonderful cousin Emily Cox Johnson

You must be logged in to post a comment.