– Brian Cox and Richard Marshall

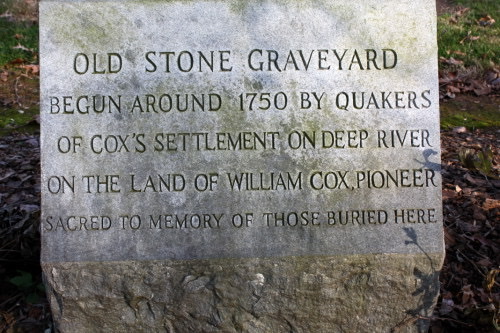

There’s a memorial at a colonial era cemetery just south of Ramseur, North Carolina, that reads:

OLD STONE GRAVEYARD

BEGUN AROUND 1750 BY QUAKERS

OF COX’S SETTLEMENT ON DEEP RIVER

ON THE LAND OF WILLIAM COX, PIONEER

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF THOSE BURIED HERE

William Cox is our sixth great-grandfather and the pioneer recognized on this stone. In fact, William, his sons, and a handful of related Quaker families were the first people of European descent to permanently settle the Deep River area of today’s Randolph County. But who were these Quakers, why did they choose the area, and what land exactly did “Cox’s Settlement” comprise?

Pennsylvania and Delaware Roots

Answering these questions begins with 1681 when the English King Charles II settled debts owed to Sir William Penn by granting land in present-day Pennsylvania and Delaware to Penn’s son, Quaker activist William Penn.1 The younger William Penn became the proprietor of Pennsylvania, an area of more than 45,000 square miles, and used the promise of land ownership and religious freedom to persuade Quakers to leave England for America.

Quakers, or the Society of Friends, were dissenters of the Church of England and believers in total equality. In a society where allegiance to the Crown was paramount, Quakers would not bow to nobles, refused to take oaths, and objected to military service. When Penn was granted the land in America, many Quakers were eager to seize the promise and hope of a new society. It’s estimated that 23,000 Quakers migrated to England to the Delaware Valley2 area between 1675 and 1725.3

In 1699, Penn divided and gave 30,000 acres to his children, daughter Letitia and son also named William. William received 14,500 acres in Chester County and Mill Creek Hundred.4 The remaining 15,500 acres, described as ”a certain tract of land situated on the South side of the Brandywine Creek, in the province of Pennsylvania,” was given to Letitia.5

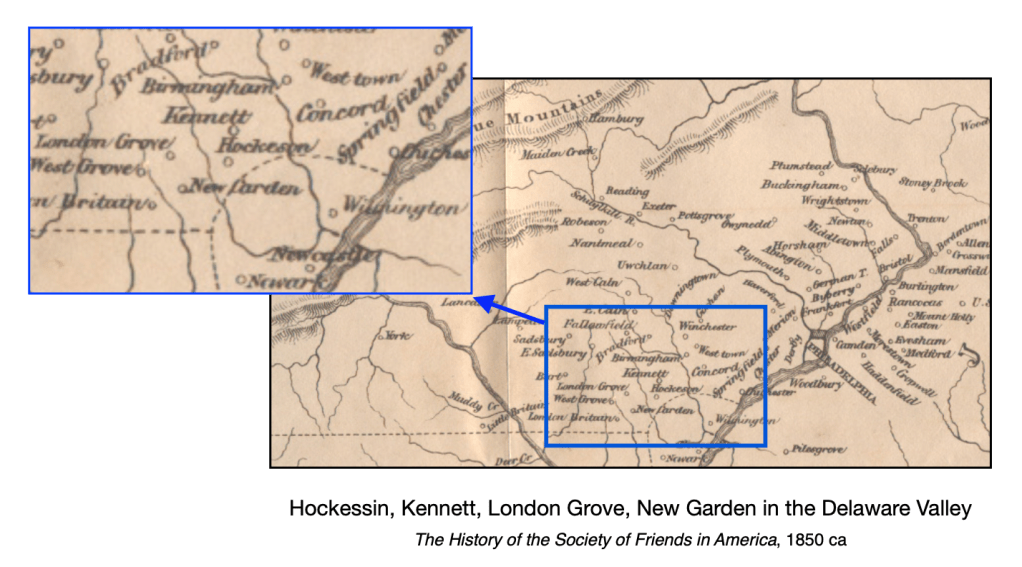

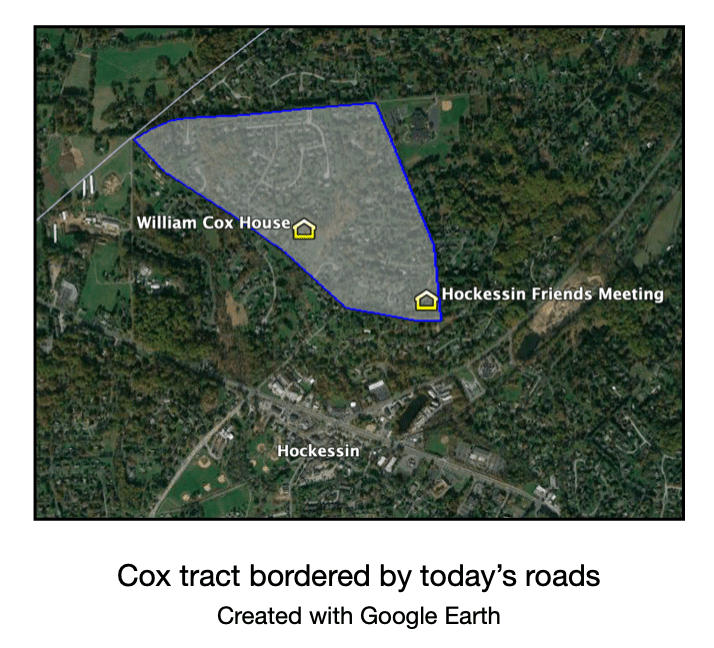

In 1721, William Cox completed a transaction with Letitia’s legal representatives for 300 acres in New Castle County. (William’s father was also named William, but subsequent transactions among Quaker land owners suggest the conveyance is to the younger William.) Delaware historians place the tract northeast of today’s downtown Hockessin, Delaware, bordered roughly by Old Wilmington, Meeting House, and Benge Roads.

William Cox married Catherine (or Katherine) Kinkey in 1716 and was living in a simple structure on his tract of land by 1722. William’s brothers John, Thomas and Richard lived on adjacent farms in London Grove. Sister Amy and her husband John Allen also resided in the area near Kennett Friends Meeting. Surnames of other local families include Dixon, Lindley, Scarlett, Mofffit, Hussey, Crawford, Garretson, Comer, and Allen. Many of these names will become common in North Carolina records within a few decades.

William replaced his first dwelling with a 2 1/2 story brick house in 1726, known as “Occason.”6 In a 2016 interview, current owner Pete Seely notes that Cox built his house near a Native American encampment known to have existed in the area.7 Quaker leaders had established good relationships with local tribes for several decades, and there’s no evidence of conflict with the Cox family.

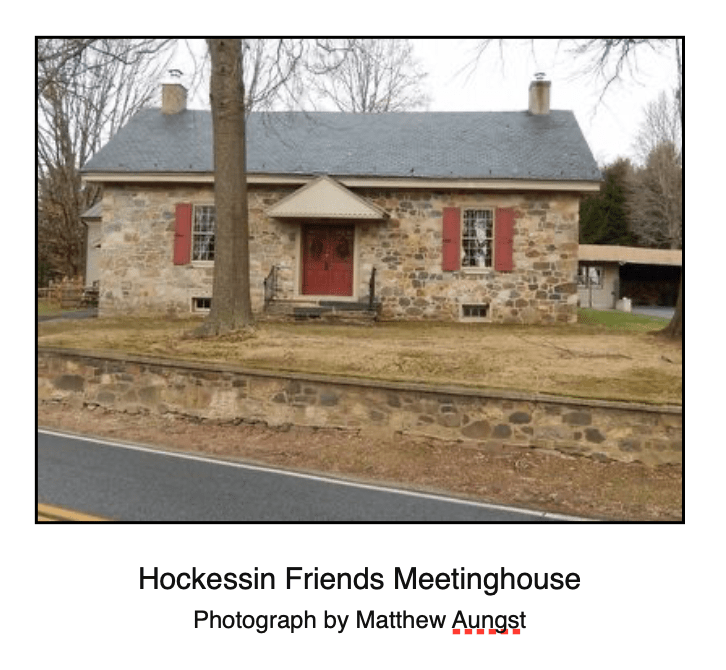

By 1730, the house was the meeting location of area Quakers. This community of Quakers soon grew large enough for the Hockessin Friends Meeting to be erected in 1732 on land donated by the Cox and Dixon families. Early Quaker families of Pennsylvania and Delaware were tightly knit with the meeting house being a community focal point. Wheat and corn were the leading crops among the farming families, and skilled tradesmen built mills to harness the power of the area’s numerous streams for processing agricultural resources.

Road to the Carolinas

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what pushed Cox and other Quaker families to leave a successful and established community for the unknowns of the southern backcountry. It was likely multiple factors: religious changes among the greater population, declining Quaker influence in matters of governance, slavery, or perhaps increasing tensions among colonists. Whatever the reason, Quaker migration from the Delaware Valley to southern destinations increased steadily during the 1730s and 1740s.

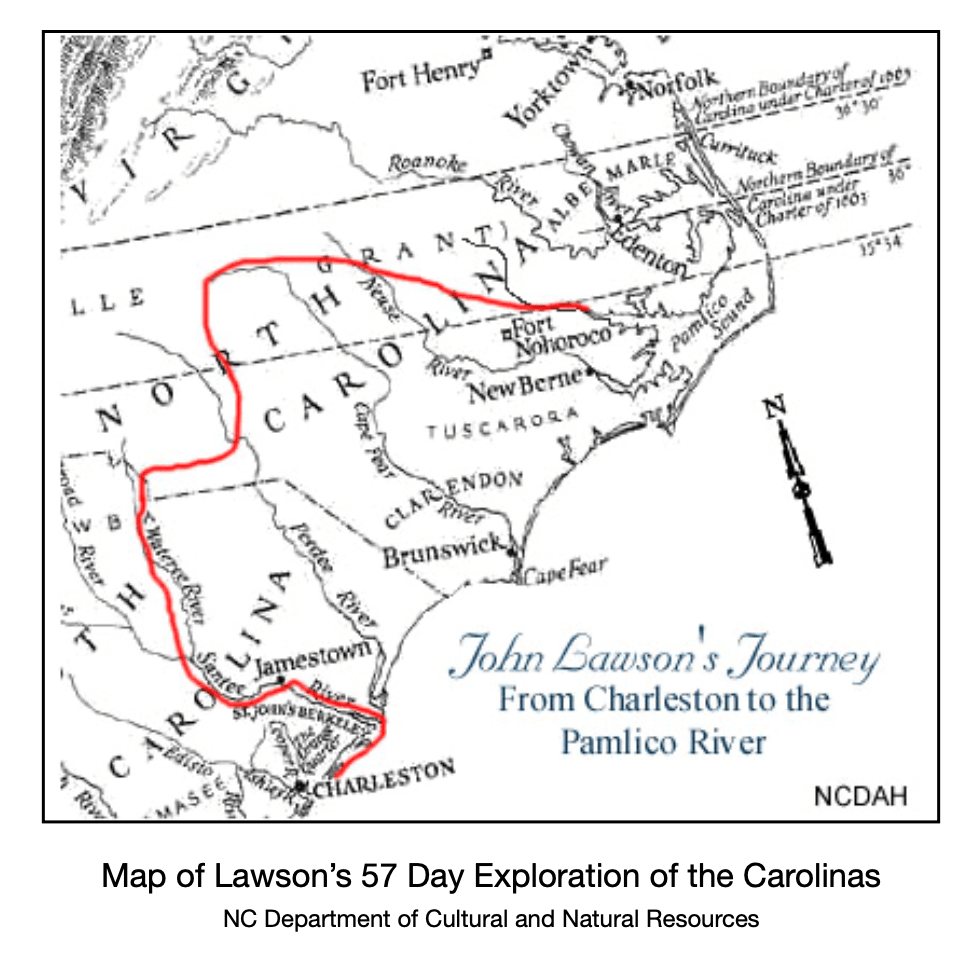

Quakers were settling in eastern North Carolina as early as 1680, but their arrival in Piedmont North Carolina was mostly after 1740. Explorer John Lawson, who later became the official surveyor of the Carolinas, documented the good soil, timber, and game after his 1701 expedition. Pennsylvania area hunters also frequented Virginia and the Carolinas.8

Much like the westward migration in the 1800s, people heading south during the early to mid-1700s were undertaking a difficult and dangerous journey. Author Bobbie Teague writes in her book, Cane Creek Mother of Meetings:

“The first of the settlers from Pennsylvania and Maryland must have made the journey by horseback and on foot and transported supplies on pack animals. Mothers with small children rode horseback while the men often walked. Traveling was fairly easy through Virginia; however, the way grew more difficult the farther south they came.”9

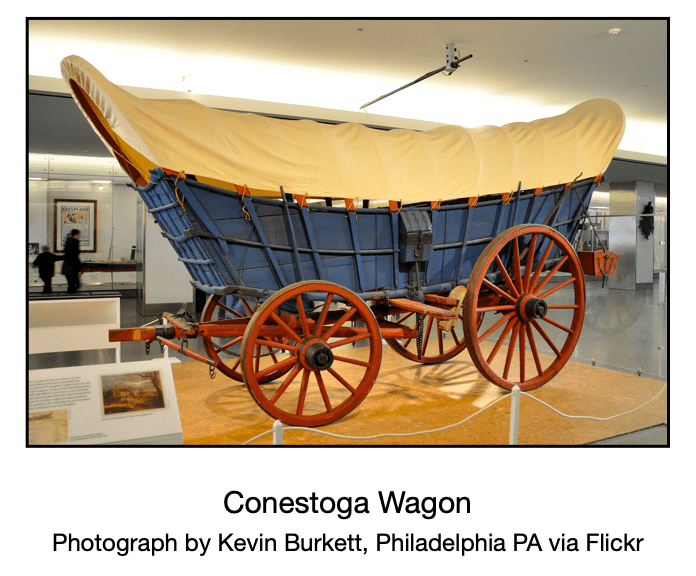

The availability of a new innovation, the Conestoga wagon, facilitated the southward movement of families.10 German settlers introduced this sturdy covered wagon that was generally pulled by a team of horses or oxen. This style of wagon became the primary transportation of people and goods until the development of the railroad.

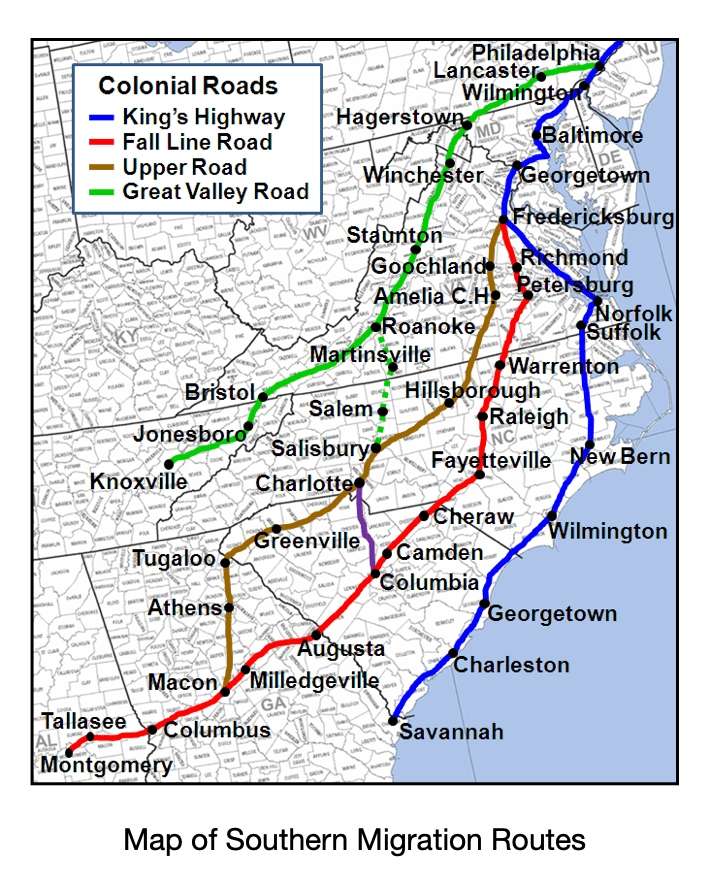

Quakers traveling through Virginia to the Carolinas followed the “Fall Line Road” or “Upper Road,” with the Upper Road being a frequently used route to take advantage of the land grant opportunities in the North Carolina Piedmont.11 Settlers tended to relocate with people from the same location and background, no doubt finding comfort in the sense of familiarity as they ventured into the unknowns of the backcountry. However, the opportunity for land with plentiful resources outweighed the risks of the challenging move.

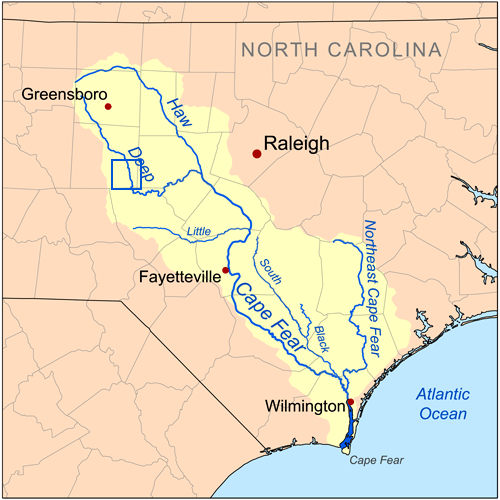

There was almost certainly advance scouting, including the building of basic shelters, before relocating entire families by wagon. North Carolina’s Piedmont is gently rolling land with forests of oak, hickory and pine bordering rich bottomlands. People exploring for new opportunities found the Piedmont land superior to the swampy and sandy coastal plain. The tributaries of Haw and Deep Rivers, including Cane Creek, near today’s Snow Camp, and Mill Creek in southern Randolph County were particularly attractive to the Quakers with farming and milling skills.

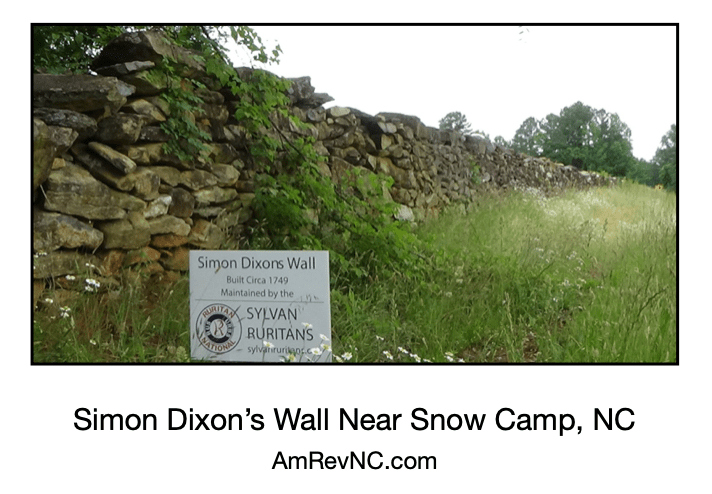

Twenty-one-year-old Simon Dixon is an example of these early visitors. In 1749, Dixon built a simple cabin and cleared land on Cane Creek, but returned to Pennsylvania in 1752 and married Elizabeth Allen.12 Simon was most likely one of several Quaker men scouting and claiming land before bringing their families.

There is no record or diary of the trip by the Coxes or neighboring families. William and Catherine’s sons, Harmon, William Jr, John, Solomon, and Thomas, all appear in North Carolina records around the same as their father. Daughters Rebecca (John Dixon), Margery (Isaac Nichols), and Martha (William Terrell) remained in the Delaware Valley with their husbands. The youngest daughter Mary was only 15 years old in 1750 and presumably made the trip with the family. She wed James Lindley in 1753 and lived near Cane Creek before relocating with her husband to South Carolina.

Quaker records show William Cox received a certificate from the Kennett Monthly Meeting on July 4, 1752 to be presented for acceptance at the Cane Creek Monthly Meeting. He was accepted at Cane Creek on February 3, 1753. His daughter Catherine and Eleazer Hunt petitioned the New Garden Friends Meeting for marriage in 1752, so it’s reasonable to conclude William relocated to North Carolina sometime before that date.13

Quaker records are silent regarding William’s wife Catherine. Like William, she was issued a certificate in 1752 from the Kennett Monthly Meeting for presentation to the Cane Creek Friends, but is not recorded as being received by Cane Creek. Perhaps Catherine died before the move to North Carolina was complete.

Granville Land Grants

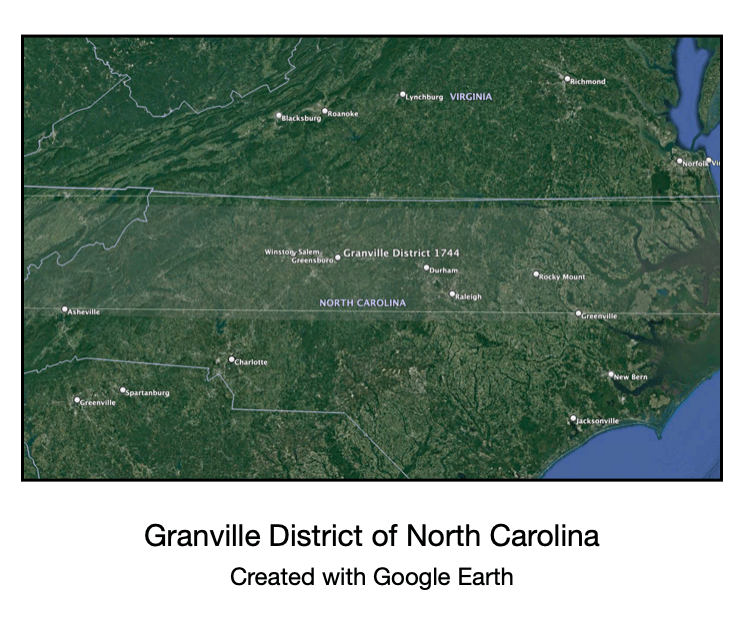

In the 1660s, King Charles II gave eight English noblemen, the “Lord Proprietors,” the rights to a large area of land called “Carolina” stretching from southern Virginia to northern Florida. By 1728 all of the Proprietors’ land had been returned to the Crown except the share originally granted to Sir George Carteret. His heir, John Lord Carteret, the second Earl Granville, retained rights to a wide stretch of land between the present Virginia-North Carolina border and a line about 65 miles south. This area became known as the Granville District, and grants of unclaimed land were made beginning in 1748.14

Quaker settler George Williams secured 640 acres on Cane Creek in 1749.15 The following year, Anthony Chamness, John Pike, and John Wright also pursued grants in the area.16 To the southwest of Cane Creek, Herman Husband17 began assembling a portfolio of 18 separate grants, most of which were on or near Deep River and its Sandy Creek tributary.18

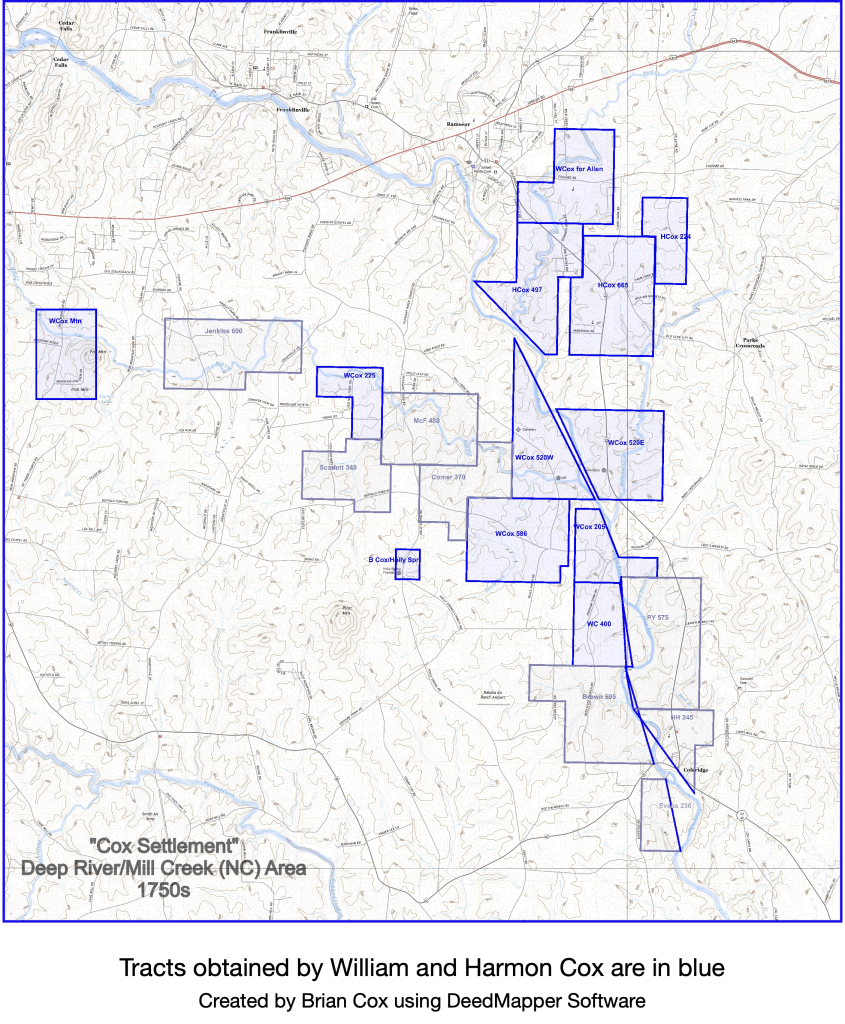

William Cox, his sons, and related families pursued Deep River grants south of Husband’s claims, focusing on the tributaries of Mill and Millstone Creek. While we cannot offer concrete evidence, it’s very likely there was coordination among the core group of settlers along Cane Creek and Deep River. Most of the families were related by blood, marriage, or both in some cases. Deed and survey records often show the chain bearers to be individuals seeking claims of their own.

William secured eight Granville land grants in the 1750s. The first four, obtained in 1754-55, totaled over 2000 acres in today’s southeast Randolph County spanning both sides of Deep River and parts of Mill and Millstone Creeks. He and his sons likely settled on the land several years before the official recording of the deeds, building the first of several grist mills.

Four more grants were recorded in 1757. The first tract was 225 acres on Mill Creek adjoining land settled by fellow Delaware Valley Quakers William McPherson (McFerson), Joseph Comer (Comber), and John Scarlett.19 The Cox, McPherson, Comer, and Scarlett families all were connected by marriages. Grants obtained for 205 acres on Deep River and 375 acres at the headwaters of Mill Creek continue the waterways-focused acquisition strategy.

William also acquired 397 acres placed in a trust for Samuel Allen, the young son of John Allen III (also a Delaware Valley Quaker and cousin of the Cox family). The Allen parcel adjoins land obtained by William’s oldest son Harmon between 1758 and 1760. Harmon’s three tracts totaled 1387 acres, including a significant portion of a trading path running parallel to Deep River called Youngblood’s Road.20

Importance of Grist Mills

It’s fair to say that without gristmills, there is no settlement. Proximity to a mill was vital since the longer the trip, the longer a farmer had to be away from his crops and livestock. Ideally, a farmer would have access to a gristmill no more than a mile or two away.

The importance of gristmills went beyond the processing of grains. A farmer would wait at the mill for his product to be processed, perhaps even waiting in line during busy harvest times, facilitating the sharing of news, trade, and bartering. Mill operators often provided ancillary services such as blacksmithing, saw-milling, and the sale of basic goods.

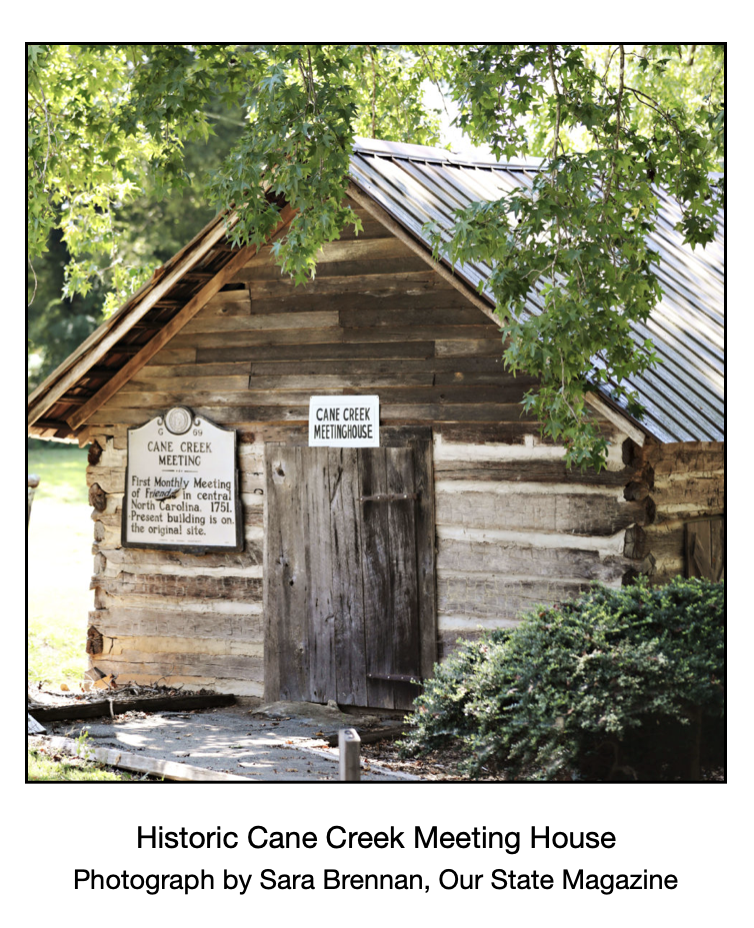

By the mid-1750s, William Cox and his sons had at least one, and possibly two gristmills, in operation on Deep River tributaries. Simon Dixon brought his millstone from Pennsylvania and had done the same on Cane Creek. Thomas Lindley also built a mill on Cane Creek, as did Herman Husband on Sandy Creek a few miles north of the Coxes. This suggests these Quaker settlers had previous experience building and operating mills, or access to a millwright.

Cox family historian Emily Johnson, who lives on land acquired via the original land grants, describes the location of the Cox Mills:

“One of the gristmills was located west of Deep River on Mill Creek and run by Thomas Cox. A second was located less than a mile away on the East side of Deep River on Millstone Creek and run by Harmon Cox, a brother of Thomas Cox. The reason two grist mills were being run by a single family so close together was the fact that Deep River is prone to serious flooding any time during the year. These ravaging floods often render Buffalo Ford, which connects the two mills, impassable for several weeks at a time.”21

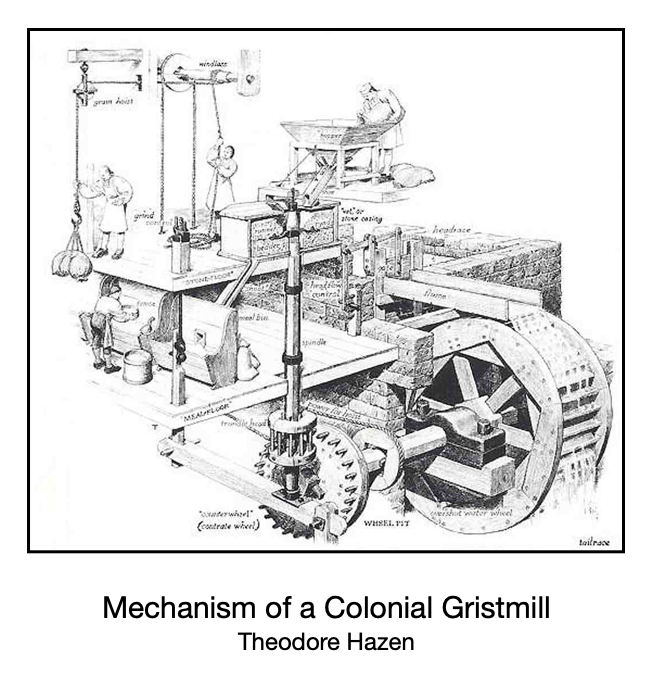

Building a gristmill in Colonial times was no small task. Skills in carpentry, masonry, and hydraulics were necessary, and most of the construction materials had to be sourced on or near the building site. Master Millwright and historian Theodore Hazen writes:

“Foundation walls were erected. Logs were cut and fashioned into beams, boards, and shingles. Pillars were constructed to support the water wheel shaft. Only the millwright had the knowledge of what woods were best used for various mill parts. The water wheel, gears, and bearings made. A dam, mill race and or a sluice box was constructed. Finally the mill was ready to be set into operation.”22

A Place is Named

While the full extent of services provided by the Cox mills is uncertain, the name “Cox’s Mill” became an identifier of the general area. “Cox’s Mill Creek” is found in the descriptions of land grant surveys of the 1750s, meaning there was enough significance to this specific location to be a reference point.

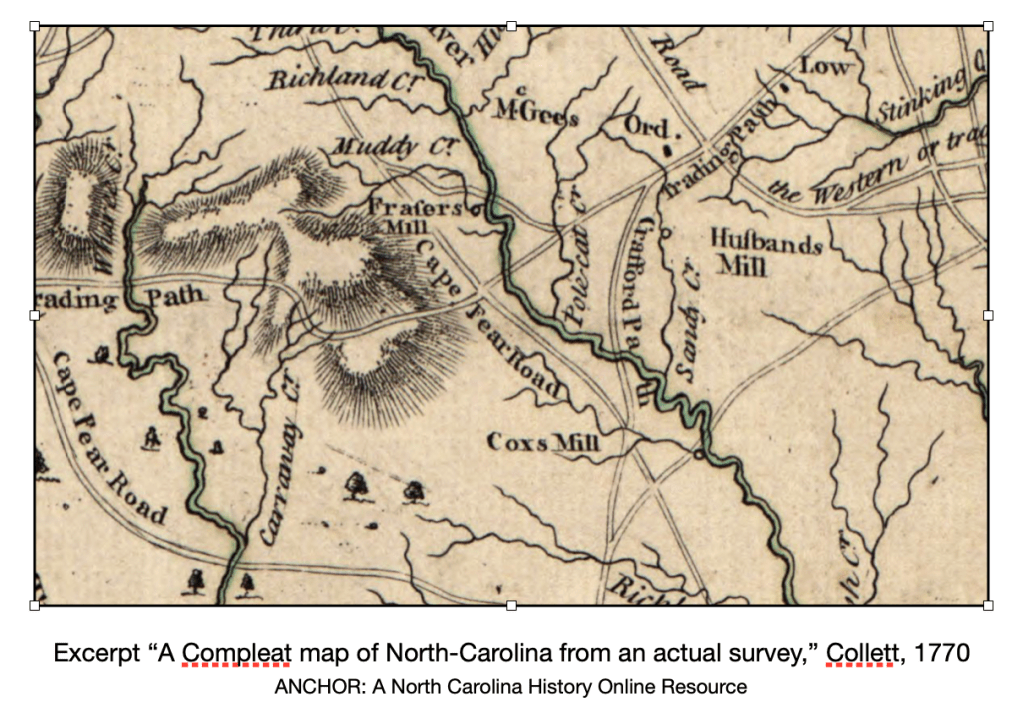

Randolph County historian Mac Whatley points to other notations, such as Orange County Court minutes for Nov. 1763 ordering a “Road be laid out from Coxes Mill to Collinses Road.” It is also one of the few Piedmont area mills on the Collet Map of North Carolina in 1770.

Mentions of “Cox’s Mill” continued through the 1760s as the location for Regulator committee meetings, and the 1770s as home-base for Tory leader David Fanning. In the aftermath of the battle with Regulators in 1771, Royal Governor William Tryon gave orders to “go to Cox’s Mill and secure all the flour there for his Majesty’s service.”

During the Revolution, Cox’s Mill was declared a public store and protected against destruction by either army. It is also the general location where General Baron de Kalb and the Continental Army camped in 1780 while awaiting the arrival of General Horatio Gates before the ill-fated battle at Camden.23

By the 1760’s, ”Cox’s Settlement” appears as a term describing the Deep River and Mill Creek area. Quaker historian Bobbie Teague writes,

“Mill Creek Meeting24 was located in Cox’s Settlement in an area which later became Randolph County.” 25

This reference in Cane Creek Meeting records seems to be the earliest written record of Cox’s Settlement. The notation implies readers would understand the location reference without additional elaboration, suggesting it was commonly used among settlers in the area. Cox’s Mill and Cox’s Settlement (and sometimes Buffalo Ford) continue as interchangeable names for the area for the next few decades, but a new name appears before the North Carolina General Assembly in late 1797.

Coxborough

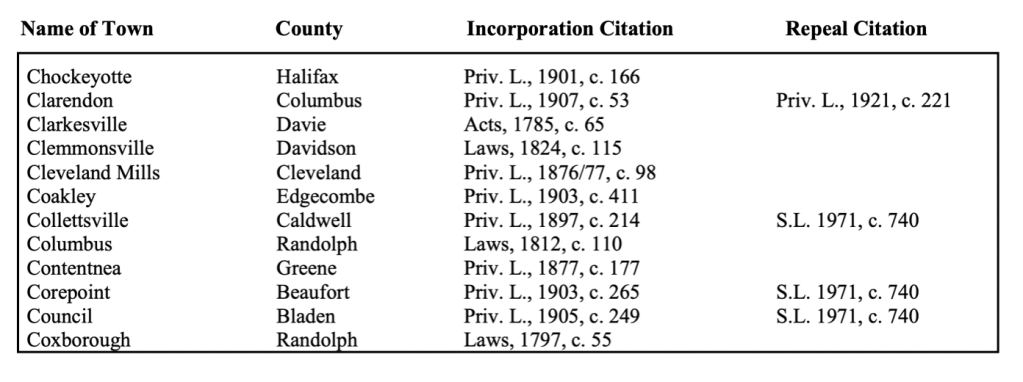

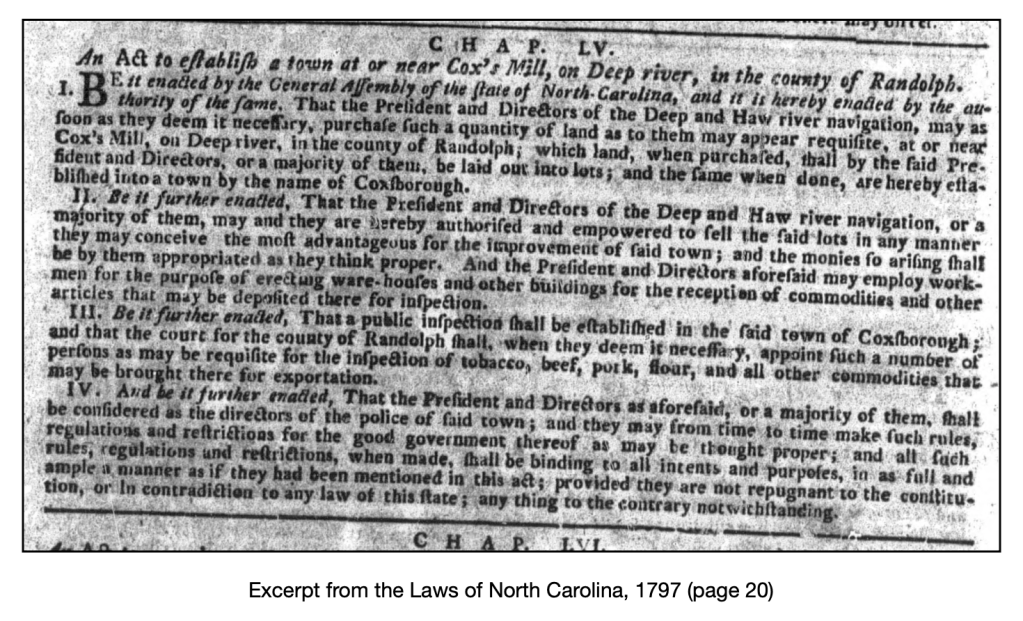

Between November 20 and December 23, 1797, the North Carolina General Assembly convened for the 22nd time (total) and 4th time in the state capitol of Raleigh. Among the items approved at the session was the establishment “at or near Cox’s Mill on Deep River in the county of Randolph” a town that would be called “Coxborough.”

River corridors were viewed as opportunities to improve the transport of goods and raw materials to and from the coastal region. The General Assembly created the Deep and Haw River Navigation Company in 1796 to improve navigation on the Cape Fear River above Fayetteville, including the lower parts of the Deep and Haw Rivers.26 Family historian Emily Johnson describes the plan:

“This area did a lot of trading in Fayetteville and river travel would have been much easier than land travel with wagons. The story was that locks would be built up and down Deep River to make the river navigable. Deep River was deep in places, rocky in others, so boats hauling goods would not be able to travel up river very far.”

The “act to establish a town at or near Cox’s Mill, on Deep River…” authorizes the Deep and Haw River Navigation Company to build a hub of commerce with “ware-houses and other buildings for the reception of commodities.”

All of this, of course, was contingent on the navigation company implementing improvements needed for the river to be a transport option. By 1830, the company had decided to focus on river improvements between Fayetteville and Wilmington, and any thoughts of a “Coxborough” were abandoned. However, the list of “North Carolina Incorporated Towns Whose Charters Have Been Repealed or which are Currently Inactive” shows “Coxborough” was never formally repealed.

Epilogue

The post-Revolutionary War period was one of transition with more westward population movement and early signs of industrialization. Asheboro became the Randolph County seat in the 1790s, and the first Superior Court session was held in 1807. Cotton mills supplanted grist mills as commercial hubs along Deep River with the towns of Franklinville, Cedar Falls, Randleman, Coleridge, and Allen Falls (Ramseur) forming around the mills.

Many descendants of the early residents of Cox’s Settlement relocated to these new towns trading farming for a working wage. Others joined the westward population movement looking for new opportunities (and land) in Tennessee, Ohio, and Indiana.27 Education allowed subsequent generations to pursue opportunities hardly imagined by the early settlers. Within a few generations, Cox’s Settlement faded into a historical footnote. However, much of the land obtained in the mid-1700s by the Cox family is still in family hands, including locations of the Colonial era mills.

On May 26, 2010, the Mill Creek Friends Cemetery was officially recognized as a Randolph County Cultural Heritage Site, joining Buffalo Ford and the Harmon Cox mill site. The cemetery lies on land owned by an Allen family descendant and is the resting place of approximately 200 people, including William Cox and his son Harmon. Some graves are only marked with a simple stone, and a complete record of burials has been lost to time or doesn’t exist.

But the history of William Cox and fellow Deep River settlers is worth remembering.

Sources of note:

You must be logged in to post a comment.