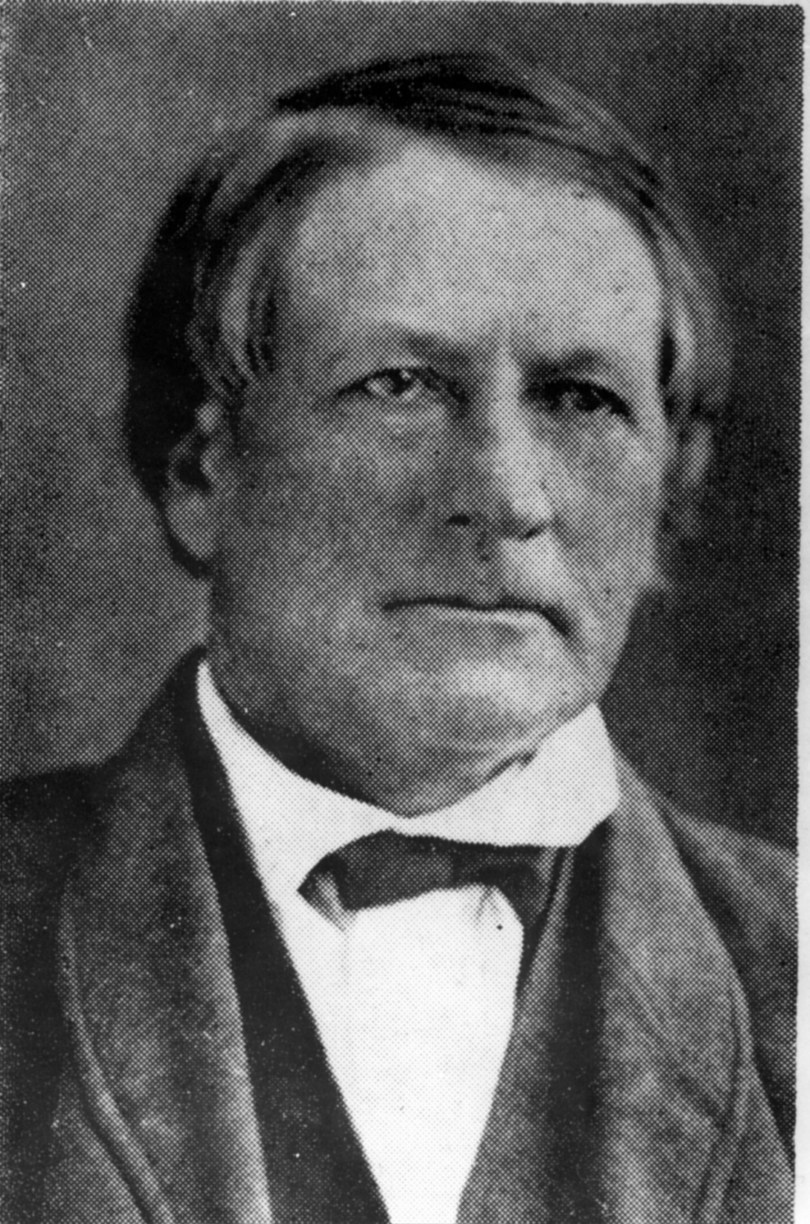

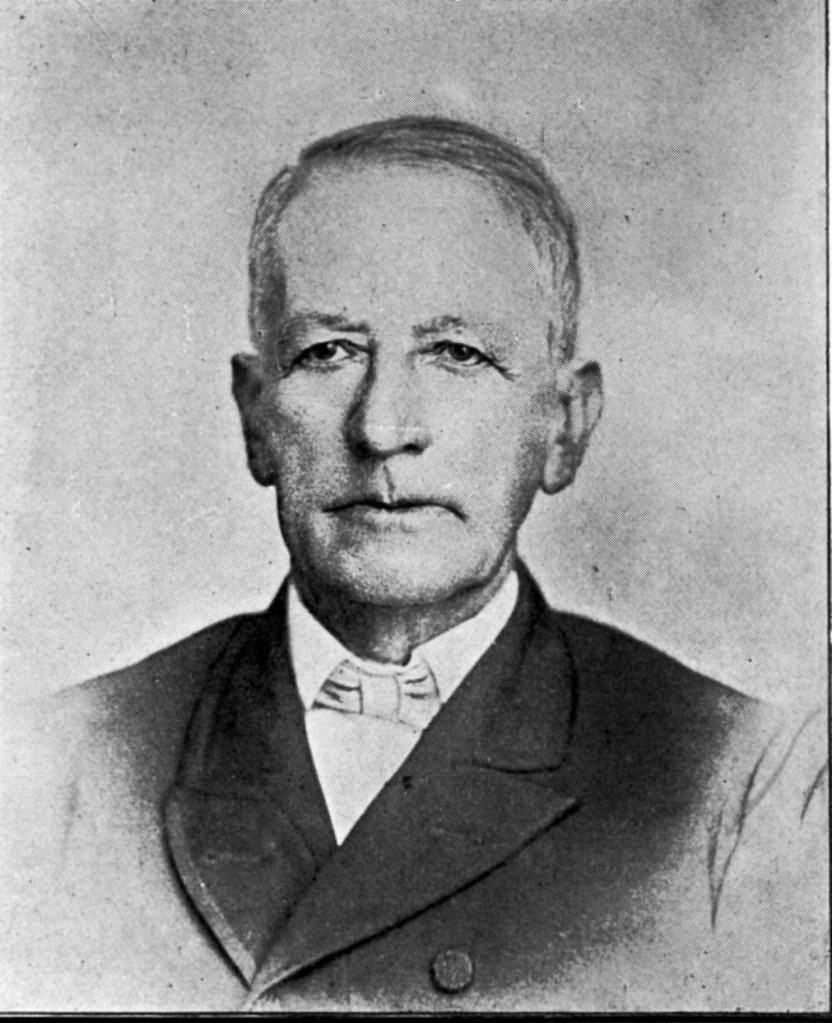

Isham Cox is an ancestor I’m meeting for the first time. I learned of his distinguished life while researching Quaker dissent during the Civil War, and am a little surprised that I did not know his accomplishments until now. (I’m posting this before a visit to Guilford College later this Spring to review his documents on file in the school’s archives, so there could be updates.)

Isham’s Childhood

Isham was born on November 5, 1815 in eastern Randolph County (NC) on land acquired by the Cox family in the 1750s. The son of William Cox and Lydia Branson Cox, and grandson of my 5th great grandparents Thomas Cox and Sarah Davis Cox, Isham is a first cousin 5X removed. He was the ninth child born to William and Lydia (their firstborn died as an infant).

Three months after Isham was born, Lydia and his oldest brother Levi died on the same February day in 1816 of the “cold plague,” a common term of the period for flu and pneumonia. Both are buried in the Mill Creek Cemetery (Old Stone Graveyard).

As Lydia approached death, William asked about her wishes for baby Isham. William was already 45 years old with a handful of kids in the home. Lydia instructed him to give the infant to her sister Rebecca Branson Pugh and her husband Thomas.

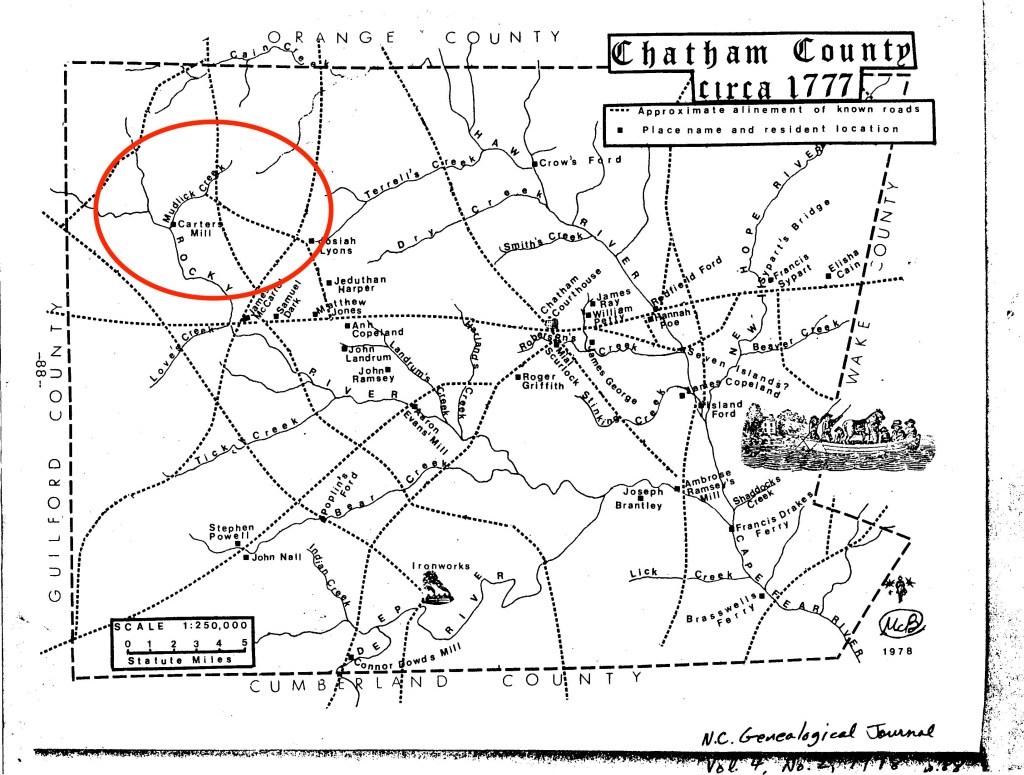

Thomas and Rebecca lived in the Rocky River community in western Chatham County, NC, and like Isham’s birth parents were dedicated Quakers. (Contrary to the pacifist tenets of the Quaker faith, relatives of Thomas and Lydia were also involved in the Regulator skirmish a generation earlier). The Pughs raised Isham with their four daughters and provided him with as much education as they could given the scarce options. Isham writes in his memoirs:

“The concern manifested by them in restraining and counseling me whilst in the slippery paths of youth proved under the Divine Blessing to be a means of keeping me in the way of life. I was sent to school sufficient to acquire a pretty thorough knowledge of the first rudiments of an English education but was privileged to study Grammar or the higher branches.”

Before Rebecca died in 1836, she asked Isham to be her daughter Rachel’s “benefactor,” a request Thomas repeated as his health declined a decade later. (Thomas died in 1846 from “dropsy” which means he likely had congestive heart failure.) I’ve yet to find a record specifically stating a disability for Rachel, but she appears on census records as a member of Isham’s household until she died in 1862 and refers to living in Isham’s home in her will.

Marriage, Children, and Early Work

Isham married Lavinia Brower in 1837. He described their courtship in his memoirs as follows:

“In the 12th month 1835 I accidentally fell in company with Lavinia Brower whose company and deportment was so captivating and withal so congenial to my mind that a proposition to renew our acquaintance was acceded to; each succeeding visit proved conducive to the strengthening of our attachment for each other until we were fully persuaded that it was the will of our Heavenly Father that we should become helpmeets to each other through life’s uneven journey.”

The marriage presented a couple of complications. First, Lavinia’s father owned slaves and second, she was a Methodist. Officially Isham was a member of the Cane Creek Friends Meeting, but he lived near Rocky River and attended a preparatory meeting established in that area. Isham described their agreement to attend services of both faiths:

“We believe it to be our duty to our Heavenly Father to be diligent in attendance of our religious meetings. It therefore became a settled matter with us to go together; and as the Friends meetings were regularly held twice a week we were more frequently seen there, but as occasion offered we attended of her people.”

Isham’s primary occupation was farming, but he was also a teacher during winter months. He and Lavinia had seven children: Rebecca (1838), Lydia (1840), Leanna (1841), Mary (1843), Alfred (1845), Artilla (1850), and Dougan (1854).

In 1847 Lavinia became a member of the Friends and both she and Isham were later appointed elders. (Apparently, any previous Brower family concerns and objections about the Quakers were set aside.) Around 1850 Lavinia’s father was among the investors in a new textile mill built on Deep River in today’s Town of Ramseur. Isham became an “agent” at the Deep River Manufacturing Company involved in the procurement of materials and sale of finished goods. The census lists his occupation as “merchant” in 1860, but he was farming again by 1870. Judging by the time Isham spent during the Civil War years advocating on behalf of Quaker conscientious objectors, it’s likely he separated from the mill before or during the war.

New Garden School

Isham was very interested in education and was asked to serve on the Board of Managers of New Garden Boarding School in 1857. The school was founded in twenty years earlier to serve the large Quaker community and admitted both boys and girls, which was not the norm in those days. Unfortunately, 1857 was also a year of significant downturn for the United States economy and the school had a large ($25,000) debt problem. The school’s superintendent was dismissed in 1859, and the property was in danger of being sold. Solving the problem subsequently fell on Isham’s shoulders.

Isham wrote to and visited Friends meetings in North Carolina’s “Quaker Belt” and appealed to northern Friends in Philadelphia and Baltimore during fundraising trips. As he was making headway, the job became even more difficult with the outbreak of the Civil War, but by 1863 was able to settle all but a $300 debt for which the creditor refused payment with paper money. New Garden not only survived, it continued operation throughout the war without missing a day.

In 1865 Isham reported to the school’s trustees:

“This report shows a liquidation of all debts against the school prior to 1864. And in humble gratitude to our Heavenly Father, the agent hereby tenders his sincere thanks to all to whom they are due.”

Dorothy Lloyd Gilbert wrote in her 1917 book Guilford: A Quaker College:

“The brow of a financial agent is not often adorned with laurels, and Isham Cox would have been most uncomfortable wearing the victor’s crown instead of the broad brimmed hat, but he deserved it.”

Quaker Values and the Civil War

Before and during the Civil War the New Garden Meeting openly opposed slavery and participated with other sympathetic Friends as part of a network helping escaped slaves flee to free states. The woods behind New Garden Boarding School is now known as a key stop on the Underground Railroad in North Carolina. However, harboring fugitive slaves was against North Carolina law and the rumored assistance of Quakers angered many of their neighbors.

Quaker historian and author Hiram H. Hilty wrote that Isham received a threatening letter from “A Slaveholder” accusing him of being a friend of noted abolitionist Daniel Worth. In expressing his disgust the letter writer reminded Isham that his wife was from “one of the worthiest families of Randolph County” who were also slaveholders. (I have written to the Guilford College archives seeking a copy of the letter). Regardless of harassment Isham remained faithful to his beliefs.

During the Civil War Isham was a tireless advocate for Quakers claiming to be conscientious objectors. When fighting began in 1861 Quakers could pay $100 instead of militia duty or work in a support capacity such as providing labor for hospitals. (State Treasurer and future NC Governor Jonathan Worth, raised a Quaker, arranged for many to serve by providing labor at Wilmington salt works.) But by 1862 it became obvious to Confederate leaders there would be a manpower shortage without a law requiring military service. The 1862 Conscription Act made all white males ages 18 to 35 subject to three years of service and added two years to the service requirement for those already enlisted in the military. The original act did not exempt any denomination on religious grounds, so North Carolina Quakers sent a delegation, of which Isham Cox was a member, to Richmond to meet with members of Congress.

Shortly after the delegation visited Richmond, the Confederate Congress passed a law exempting all ministers, Quakers, Dunkers (German Baptists), Mennonites, and Nazarenes who would furnish a substitute or pay a tax of $500. (My 2nd great grandfather Calvin Cox paid the $500 tax.) A “proof letter” documenting the legitimacy of an exemption based on religious affiliation was also required.

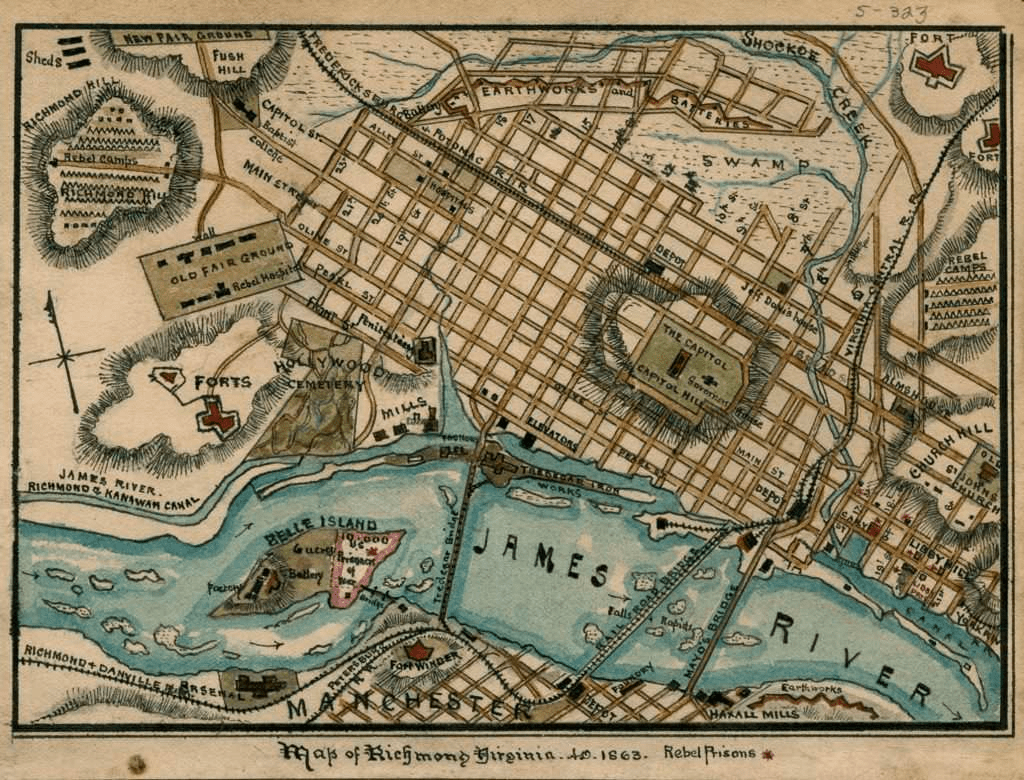

Some Quaker men were already in military camps and their proof documents had to be submitted and approved to be released from service. In January 1863 a committee comprising Isham, John Crenshaw, Nereus Mendenhall, John Carter, and Allen Tomlinson was established by the Friends to petition the Confederate Congress for relief. Crenshaw was a minister living in Richmond, VA and knew some of the leading men in the Confederate government. Isham and his fellow Quakers specifically wanted the release of six young Quakers at Camp Lee in Richmond. (Camp Lee, named in honor of Revolutionary War hero Henry Lee, was a location where newly drafted men reported after the Conscription Act. It was previously a fairground.)

The elders found one of the men, Mahlon Thompson, in very poor condition at Camp Lee. Unfortunately Mahlon was an early Quaker casualty of the Civil War. Isham wrote:

“We started homeward suffering much with cold and detentions on the road and Mahlon growing more and more poorly. He deceased soon after reaching home.”

For the next four years, Isham made frequent visits to the camps and battlefields of North Carolina and Virginia to advocate for Quaker men claiming their rights as conscientious objectors. He went to Richmond and Raleigh, NC multiple times, plus Greensboro, Asheboro, Statesville, Salisbury, and Goldboro.

“Second month 24th, 1863 I went to Goldsboro and paid the Tax for Nathaniel Cox and Jeremiah Pickett and got a furlow for Thomas Hinshaw and his brother Jacob and Nathan and Cyrus Barker to go home and consult their parents and either pay the tax or return to camp, after which they concluded to return to Camp rather than pay the tax and were taken prisoners at Gettysburg Pa.”

Quaker historian Seth Hinshaw wrote that Isham “secured the release of seventy-five to one hundred men, whom he called sons, brothers, husbands and fathers.”

After the War

Isham and other Quaker leaders traveled to Baltimore in the summer of 1865 to meet with King and members of the association. Hinshaw and Gilbert write that Isham a key spokesman urging funding for “educational and spiritual interests” to be a priority. The belief was that rebuilding the educational infrastructure for Quaker children would encourage families to stay in North Carolina and stem the tide of westward migrations. Quakers also believed in the need to educate former slaves with their new freedom. Over the next decade, the Baltimore Association facilitated the establishment of schools for both whites and freedmen, including a model farm near High Point to teach agriculture

After the war, Isham continued his ministry and served several terms as clerk to the Yearly Meeting of Friends. He was a frequent speaker at Friends meetings and travelled long distances even as he was approaching 60 years of age. Isham describes his 1870 schedule as follows:

In 3rd Mo” following attended New Garden Quarterly Meeting sad iron thence to Salem had a meeting with the “United Society of Friends” (Freedmen who had applied for membership with us) and thence to Westfield, Longhill Mt Airy and where I had good Meetings, then home. And in Fourth Month attended the Meeting for sufferings and then proceeded to Visit, Deep Creek and other Meetings in that Vicinity then back by Salem and had another Meeting with the Freedmen then back by New Garden and homeward — Being solicited by the Committee having charge of the building of the New Meetinghouse at New Garden to solicit aid for the same, with the Concurrence of my own Monthly and Quarterly Meeting I started to Ind on the 15″ of 5″ mo” 1870 Stopping two days in Damascus in Ohio at a meeting of the Executive Meeting on Indian Affairs. I then went no to Ind and attended about 64 different Meetings in the limits of Indiana and Western Yearly Meeting Mostly to good satisfaction…

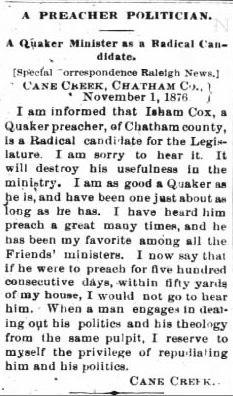

Isham adds he “took sick” on this particular trip, and that his wife Lavinia had also been “quite sick” during part of his absence. After they both recovered, Isham returned to his active travel and speaking agenda for the better part of the 1870s. He apparently was a Republican candidate for the NC legislature in 1876 drawing the ire of at least one Cane Creek resident.

The Republican Party was on the defensive for the 1876 election in North Carolina with the issues related to reconstruction. Democrats were state’s conservative party with white supremacy driving its campaign. Isham wasn’t elected.

In late February 1878 Isham was in Goldsboro when he received a telegram alerting him of Lavinia being sick. He returned home arriving shortly before her death:

I returned home immediately-arriving there on the night of the 3rd of 3rd mo” next day my Grand daughter Stella Cox died and on the 7 of 3rd Mo 1878 my dear Companion quietly breathed her last on earth.

With no one at home, it was only a few months before Isham returned to his work with the Friends. He married Pamelia Elizabeth Amick Julian in January 1779 who had been widowed several years earlier. (“Lizzie” was a few days shy of her 38th birthday, and Isham was 63.) Their only child, a daughter, was born in November of the same year but only lived four days. Isham and Lizzie later adopted a son and named him Charles Isham Cox.

During his latter years, Isham reduced the frequency and length of his travels but continued to minister, officiate marriages, and speak at funerals. Newspaper articles record his being active as late as 1892. Isham died at home at age 78 on September 13, 1894. He was buried at Rocky River Meeting, his home meeting. The Guilford Collegian wrote the following:

“He peacefully fell asleep in Jesus at his home in Liberty, N. C, on the 13th of 9th month, 1894. Through many long years of Christian service the faith had been kept and more than man’s allotted years had been given to our friend. The remembrance of him has been imperishably impressed upon the minds of all those who knew him as one full of good works; truly the good that men do lives after them. He should be an example to us of tenderness, purity, honesty, charity, sympathy, cheerfulness and love.”

An article published in the July 24, 1932 Greensboro News & Record during the school year of 1932-1933 describes how Isham’s adopted son, Charles Cox, came from the family home place near Liberty to Guilford College to deliver his father’s valuable papers and account books. (He walked most of the distance over two days.) The documents are preserved in the Friends Historical Collection.

More on Isham

Resources of note:

- The Miracle of Isham Cox, The Southern Friend Journal of NC

- Conscientious Objectors in the Confederacy

- Toward Freedom For All: North Carolina Quakers and Slavery

- Guilford College Quaker Archives

- Francis T. King and the Baltimore Association

- I Have Called You Friends

- Pioneers of the New South: The Baltimore Association and NC Friends in Reconstruction

You must be logged in to post a comment.